Hunting for Witches: from Salem to the Lower Yangtze

Thinking of witchcraft in history brings to mind images of hysterical bonnet-clad women having seizures and hallucinations in New England courthouses, poor European wenches being burned at the stake by righteous Inquisitors, and medieval Christians drowning pagans based on Monty Python-style logic. The more enlightened may picture solstice rituals at Stonehenge or the quirky lady at the New Age bookstore. And the more anthropological-minded would point out that people in cultures all over the world have and continue to use witchcraft to ostracize quirky, outcast, or otherwise undesirable people, often using them as scapegoats for disease, bad weather, acne, or bad traffic. While Chinese history is certainly no stranger to unorthodox religious movements, it generally is not the first place most people associate with witchcraft.

Of course, these modern concepts of witchcraft emerged in relation to Christianity and a concept of religion that cannot encompass the vast range of Chinese religiosities, rituals, and superstitions. Those who use supernatural means to harm others are described in culturally specific terms, but the widespread belief that such people exist and the dangerous panic that ensues when fear of them runs rampant both appear shockingly similar from Salem, Massachusetts to the Lower Yangtze Valley.

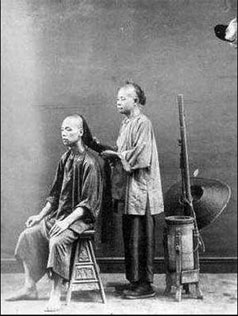

Of course, these modern concepts of witchcraft emerged in relation to Christianity and a concept of religion that cannot encompass the vast range of Chinese religiosities, rituals, and superstitions. Those who use supernatural means to harm others are described in culturally specific terms, but the widespread belief that such people exist and the dangerous panic that ensues when fear of them runs rampant both appear shockingly similar from Salem, Massachusetts to the Lower Yangtze Valley. Traditional Chinese belief holds that the soul contains two parts: the po 魄 and hun 魂. The lighter hun can drift away while one is sleeping, and it sometimes wanders too far and needs to be called back to awaken the comatose. In 1768, a rumor circulated that certain heretical monks had developed a technique to steal these souls and force their owners to do their bidding. Some alleged that workers building a bridge were enslaving souls by attaching people’s hairs or even just a paper containing someone’s name to wooden pilings, using the unfortunate soul’s power to drive the pilings into the ground. Other master sorcerers reportedly were using hair and paper to make voodoo-like dolls of numerous people. Then, they would send these enslaved minions to steal for them. (Doesn’t seem like the most imaginative use of stolen souls, but it apparently made sense to people at the time…)

In several incidents, peasants accused begging monks passing through their villages of attempting to enslave children and unsuspecting villagers. Numerous wandering monks were rounded up and searched for scissors, hair or a “stupefying powder” used to temporarily incapacitate victims for a pernicious trimming. Of course, cutting off all the hair is part of initiation for Buddhist monks, so scissors and locks of hair kept as mementos were not uncommon among monks’ meager possessions.

In several incidents, peasants accused begging monks passing through their villages of attempting to enslave children and unsuspecting villagers. Numerous wandering monks were rounded up and searched for scissors, hair or a “stupefying powder” used to temporarily incapacitate victims for a pernicious trimming. Of course, cutting off all the hair is part of initiation for Buddhist monks, so scissors and locks of hair kept as mementos were not uncommon among monks’ meager possessions.  Enough disorder and arrests resulted to draw the attention of the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor himself. Imperial involvement made this witch-hunt much more far-reaching than the one in Salem, but it functioned in an all-too-familiar way. People began accusing shady strangers and old enemies of witchcraft. Accused sorcerers were tortured into confessing and implicating others. Such forcefully obtained evidence portrayed a vast conspiracy led by an elusive master enchanter, which further exacerbated fear, producing more accusations, more arrests, more torture and more panic. Soon, kids were ditching school and blaming witchcraft. And eventually, after multiple deaths, numerous broken bones and countless damaged reputations, confessions were recanted and survivors released from prison.

Enough disorder and arrests resulted to draw the attention of the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor himself. Imperial involvement made this witch-hunt much more far-reaching than the one in Salem, but it functioned in an all-too-familiar way. People began accusing shady strangers and old enemies of witchcraft. Accused sorcerers were tortured into confessing and implicating others. Such forcefully obtained evidence portrayed a vast conspiracy led by an elusive master enchanter, which further exacerbated fear, producing more accusations, more arrests, more torture and more panic. Soon, kids were ditching school and blaming witchcraft. And eventually, after multiple deaths, numerous broken bones and countless damaged reputations, confessions were recanted and survivors released from prison.It would be too easy to blame these events on the gullibility of the aging (and arguably senile) Qianlong who urged his magistrates to vigorously prosecute queue clippers and soul stealers and to root out the mysterious head sorcerer. But anything related to the hairstyle the Manchu rulers imposed on the populace was politically sensitive, and ridiculous-sounding movements have caused immense disorder and suffering throughout Chinese history. Indeed, a few decades later, a man claiming to be Jesus Christ’s little brother would found a “heavenly kingdom” provoke one of the bloodiest conflicts in world history.

Indeed, nightmare scenarios like this do not result from the frightening power of government run amuck or the eerie potential of the supernatural, it is the much more real, omnipresent, and terrifyingly powerful potential of humans to turn on each other. It would be nice if there were only a few isolated schemers murmuring incantations and hatching nefarious plans for petty theft and bridge building. Instead, whole villages of apparently decent people actually beat up and even killed poor and dirty outcasts, neighbors turned on each other over petty grudges, and courts founded on noble virtues became coercive instruments of false accusation. And if Joseph McCarthy (or the Cultural Revolution) taught us nothing else, it is that this can happen again, anywhere and anytime. So perhaps the real reason people are willing to believe that isolated pockets of unadulterated evil live among us is that it’s a comforting thought compared to the reality that real, diffuse evil lurks inside all of us, and it too easily and too frequently congeals us into an unthinking, intolerant, and violent mob. Scary, huh?

For more on the sorcery scare of 1768 and what it reveals about Qianlong and his bureaucracy read Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 by Philip Kuhn.

Comments

Post a Comment